It's a tartanaissance!!!

10 fun facts I learned about tartan while writing my latest article for Vogue.

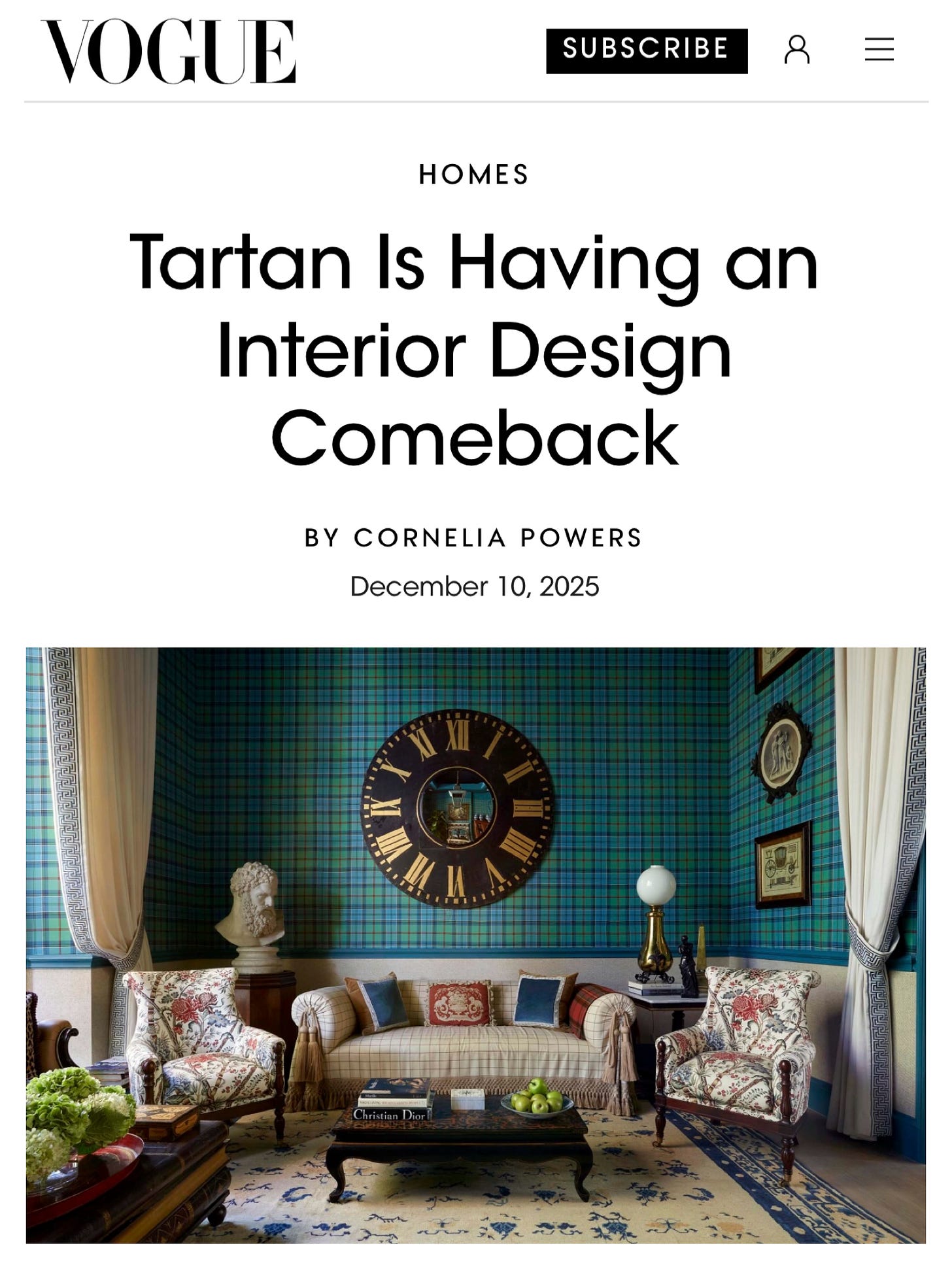

Since the third century A.D., tartan has served as a cultural touchstone for Scotland — first as a form of dress worn by Highland clans and a symbol of resistance against foreign rule, and later as a trademark of the Scottish “brand.” Over the past year, there has been a massive resurgence of tartan across fashion and design, which I recently had the joy of writing about for Vogue. In the piece (link here), I dive into tartan’s complex history while examining what might be behind this latest resurgence — or as I like to call it, our “tartanaissance.”

For today’s Substack, I wanted to share ten fun facts I learned about tartan over the past few months, plus some amazing pictures that are sure to inspire, especially now that the holidays are in full swing.

1. The origins of tartan are actually quite complex.

Tartan has been worn in Scotland since 200 A.D., though its precise origins are still unknown. While researching for my latest article, I had the privilege of connecting with Mhairi Mawell, a curator of contemporary history at the National Museum of Scotland, where she and her colleagues oversee one of the largest collections of tartan in the world. She shared that tartan has either Germanic or French roots, though Scotland was the best at embracing and elevating the pattern as its own. Over time, it emerged as a Scottish mainstay, with colors to reflect the country’s tribal networks and richly varied terrain. In the northeast, clans such as Macintosh and Robertson created patterns with pops of red sourced from local dyes, while the MacLeods and MacDonalds of the west sported tartan in earthy shades of blue, black, and green.

2. “Two over two.”

Tartan is comprised of a repeated pattern of horizontal and vertical stripes that form an interlocking grid. Unlike tweed, it is made from a “two over two” twill weave, in which one over- and under-weaves two threads at the same time. In the U.S., “tartan” is often used interchangeably with “plaid,” though they are not the same thing. Derived from the Gaelic word for “blanket,” a plaid refers to the large kilt-like cloth that is typically worn over the shoulder, often in a family tartan (hence the confusion).

Structurally, tartan is similar to madras, which can be traced to Madrasapattinam, a tiny fishing village in southern India, though there are several key differences — namely that the latter is a lighter-weight cotton that contains bolder, “bleeding” colors.

3. Tartan became so popular because it was PRACTICAL.

Among the families native to northern Scotland, tartan was favored for its practical over its aesthetic qualities. Made from wool, it was durable, water-wicking, and warm, which made it well-suited for Highland living.

4. Tartan became a symbol of Scottish rebellion.

In the eighteen century, tartan became a sign of allegiance to Charles Edmund Stuart (aka, “Bonnie Prince Charlie”), who unsuccessfully led an army of tartan-clad rebels against the British at the Battle of Culloden to reclaim his father’s (James III’s) throne in 1746. After Charlie’s defeat, the English enacted the Act of Proscription, which banned men in Scotland from wearing all “Highland Clothes”:

“No man or boy, within that part of Great Briton called Scotland, other than shall be employed as officers and soldiers in his Majesty’s forces, shall on any pretence whatsoever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland Clothes (that is to say) the plaid, philibeg, or little kilt, trowse, shoulder belts, or any part whatsoever of what peculiarly belongs to the highland garb; and that no tartan, or partly-coloured plaid or stuff shall be used for great coats, or for upper coats.”

5. Queen Victoria was (largely) responsible for re-popularizing tartan.

Inspired by the writings of Sir Walter Scott, Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert made their first visit to the Scottish Highlands in 1842 before purchasing Balmoral Castle a decade later. The couple decked virtually every room in tartan, including a grey-purple “Balmoral” tartan designed by Albert to reflect the region’s heathery terrain. What followed was what Mhairi Maxwell and her colleagues call a “Balmorization” of tartan, which quickly took over British fashion and interiors.

But why was the pull toward tartan so strong? In a paper co-authored by James Wylie and Kirsty Hassard of the V&A Dundee and Jonathan Faiers of the University of Southampton, Mhairi points to cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940), who famously wrote about how private spaces changed in the nineteenth century, transforming from impartial dwellings to a form of “world theatre.” As part of this “theatre,” the tartan popularized by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert conjured a “romantic” and sanitized impression of the past, which allowed one to maintain “illusions.”

In short, tartan became so popular because it made people feel good.

6. Look to the Donald Brothers.

In 1934, Cecilia Bowes-Lyon, the Countess of Strathmore and grandmother to Queen Elizabeth II, commissioned Donald Brothers Ltd. — a Scottish linen manufacturer based in Dundee — to produce a range of tartans based on a Royal Company of Archers Uniform, which she mistakenly thought belonged to Bonnie Prince Charlie (oh the irony!). The firm got to work and soon attracted the attention of American interior designer Dan Cooper. A founding member of the American Institute of Decorators, Cooper was one of the first designers to introduce Scottish tartan to the modern American interior. Displayed at his iconic penthouse showroom at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, his collection of tartan textiles from the Donald Brothers proliferated across homes, offices, restaurants, and airports across the United States, reflecting a style that was rooted in the Scottish diaspora yet deeply and uniquely American.

7. The 1950s and 60s were HUGE for tartan.

During the 1950s and 60s, tartan started to appear EVERYWHERE — from the stage-to-screen adaptation of Brigadoon starring Gene Kelly (1954) to the branding for 3M’s Scotch Tape. Furnishings upholstered in Anni Albers tartans took over Harvard dormitories while tartans and tweeds set the tone for Lyndon Johnson’s presidential ranch in Stonewall, Texas.

8. In the 1970s and 80s, the meaning of tartan was turned on its head.

In the 1970s, the Sex Pistols subverted the Victorian world’s fetishization of tartan by wearing deconstructed versions of the Scottish cloth designed by Vivienne Westwood. Soon, these misshaped, patched-together tartans became synonymous with the punk movement. Later in the mid-1990s, fashion designer Alexander McQueen went even further with his infamous “Highland Rape” show, dressing models in bloodied tartan to convey the tragedy of Culloden and the erasure of Highland life.

9. There is a fascinating world of tartan theory.

During our conversation and subsequent emails, Mhairi Maxwell introduced me to a rich body of academic work related to tartan. One of the most important contributions is Grids (1979) by American art critic and Columbia professor Rosalind Krauss. In it, Krauss frames the Scottish cloth as a “a tiny piece arbitrarily cropped from an infinitely larger fabric,” which extends in perpetuity, telling a never-ending story of time and place. Certainly, this story is not only about the textile, but also about the people who make it. As the practice of weaving is an extension of the maker’s physical body, Anni Albers wrote, so too is tartan a representation of our physical and intellectual abilities.

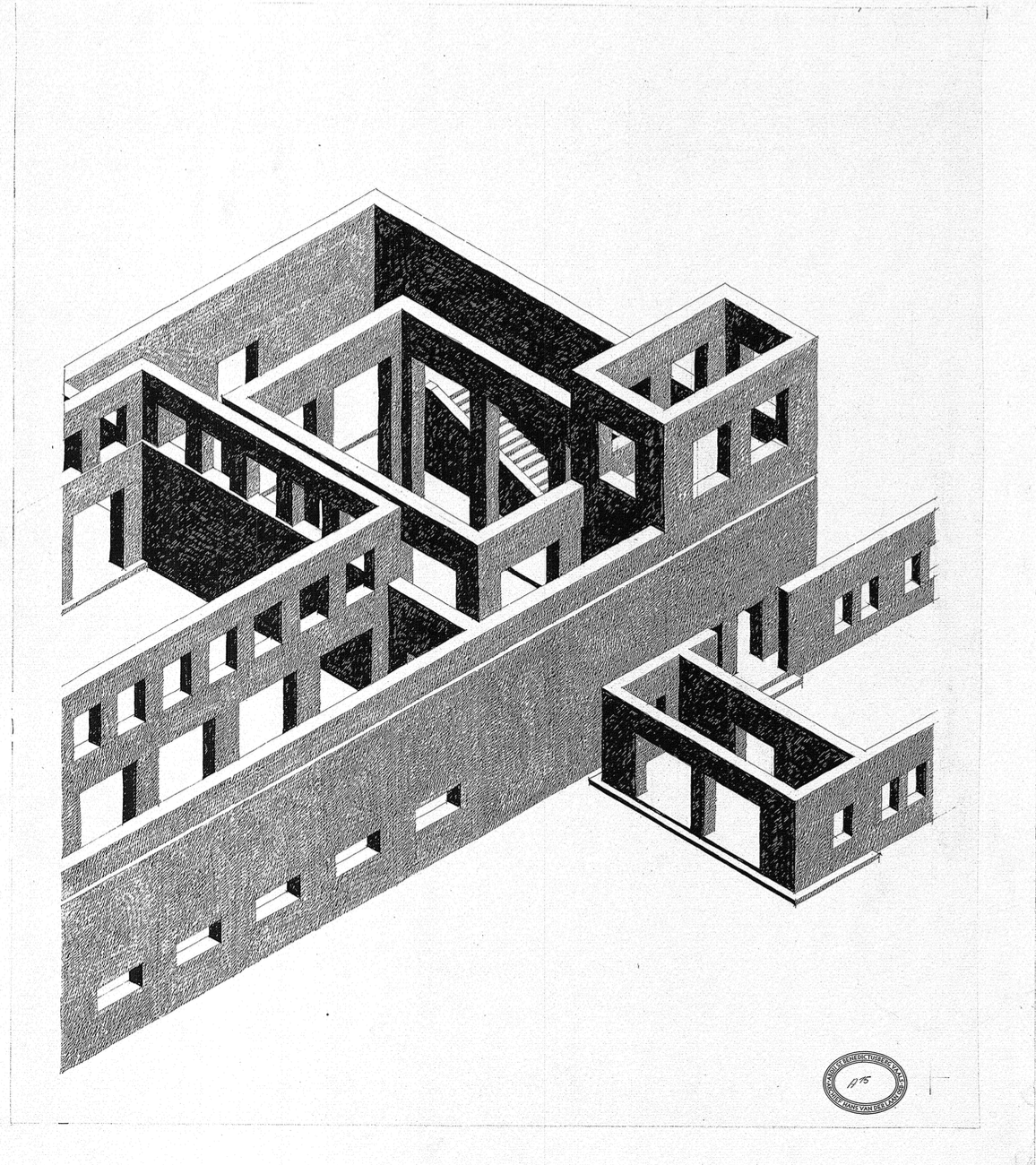

Interestingly, this body of work applies to architecture as well. Perhaps the most famous architect to draw upon tartan was Dom Hans van der Laan (1904-1991), a German Benedictine monk who invoked tartan’s “spatial superposition” in his design of the Benedictine abbey at Vaals, located in the southeastern Dutch province of Limburg. Van der Laan believed that tartan perfectly encapsulated the tension between interior and exterior and “solid and void,” making it the perfect “transcendental” design. Steeped in his Bossche School, his design of the abbey at Vaals served as a testing ground for these ideas, existing not as one space but rather a space “called upon by other spaces.”

10. Tartan will always be relevant.

To this day, tartan remains a wonderfully inclusive and fluid textile, imbued with endless layers of meaning — both literal and figurative. Embedded in Scottish history and culture, it connects us to what Mhairi Maxwell and her colleagues call “a remote yet ever-present time and place.” This sense of place has a way of reminding us all of home, no matter where we are from. In times like these, it is such connotations of home — together with tartan’s unique adaptability — that give it a particular timelessness, ensuring that it will never go out of style.

“Thank God for the Scottish,” interior designer Tony Baratta told me during our interview. And thank God for tartan!

Your friend and fellow traveler,

How to support

LINKAGE is a free, all-access newsletter, but I would be eternally grateful if you would share it with a friend and/or follow me on Instagram here.

I just love this so much. My spouse wore his ancestral clan tartan at our wedding made by a bespoke maker in Aberdeen. It continues to be his formal wear of choice.

Such fun, Cornelia! Love this piece!